1:25

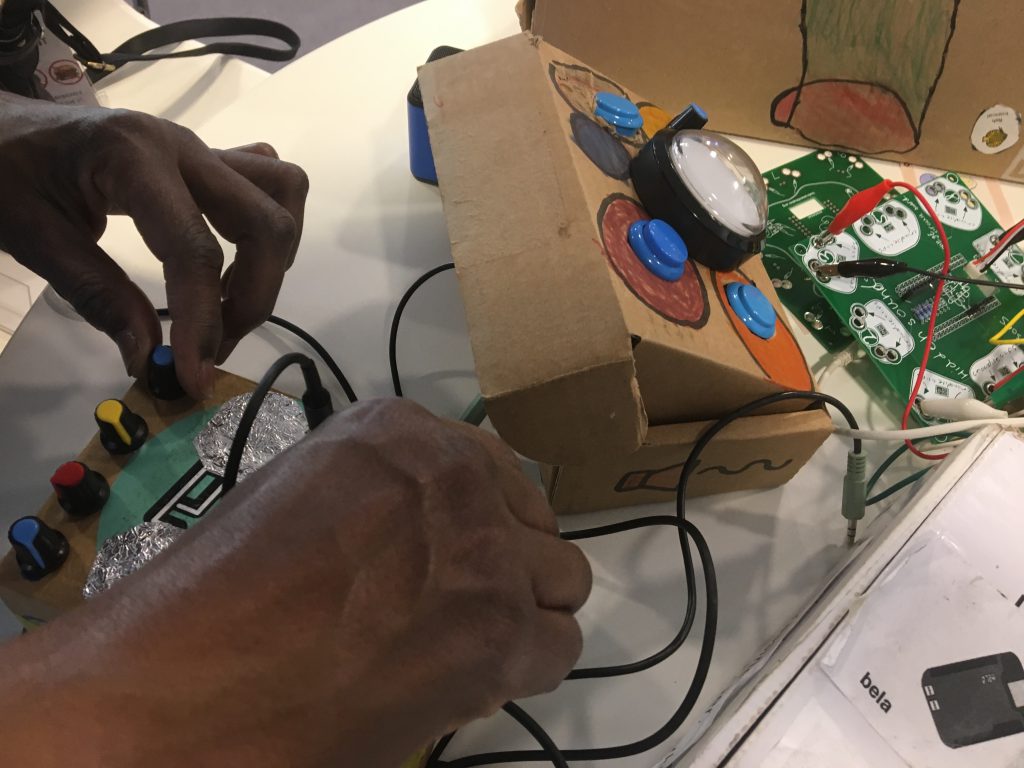

Jo: The opening piece stems from when I first jammed with Charles with colour and the cello.

So Charles was making the cello notes into colour in a studio and it just changed the way I played.

1:48

[soft cello music interwoven with the pulsating light on the video]

2:26

Jo: Yeah, it was like you said, Gift. It was quite a spiritual, soulful experience.

There’s something about light and colour that is very soulful.

So that the first piece, the UK Tree Path and the Canada Tree Walk, it’s the Dragon Cello lighting up these these lights. and it’s just spiritual and soulful and exploring, and mysterious.

2:58

And it’s about being in a sort of protective veil of mysterious light. And it’s to do with a part of neurodivergence.

I mean, I can only speak for myself, because everyone experiences it differently.

But it is rarely talked about, like, the positive side of it. And it’s about the positive side of being more sensitive.

3:31

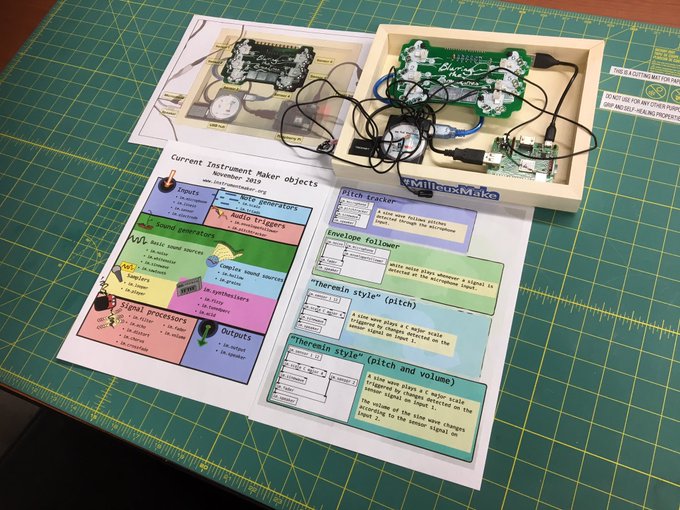

Charles: Personally, I felt really strongly connected to that, that way of, I don’t know, playing with the sound and then producing light from that.

It takes me back to why I started doing things like this in the first place.

Because it often involves something like a computer or circuit boards, or whatever.

But really, it’s just that these are the best ways I find to make something that doesn’t fit into the usual the usual norms of how we experience music.

I love stuff that’s got a continuum, say, from sound down into feeling and bass.

And when we think about vibration separately, if people are talking about kind of vibrating objects, coming from a dance music perspective,

I’m thinking well, that that’s just what we were doing back in the day, that’s just, you know…

we would be seeking to make stuff that was more like a roller coaster than a track, or something like that.

4:28

Jo: Yeah. [laughs]

4:29

Charles: And, and the light in particular, I remember wanting to get into this as a teenager, wanting to make music.

I wanted to make something that would not just take you somewhere else but maybe make people hallucinate or something.

And how would you do that through sound? How could you really play with it?

And it’s quite funny now, kind of, much, much later on, realising that music can do things to you.

And like, if it’s making you hallucinate, then that’s on the surface.

It’s like, there’s some kind of really deep change that might be taking place.

And something like this can maybe help understand that with the verbal communication on something, which usually takes priority, like I think you mentioned earlier, on Kate, there’s a different way of communicating that we might not be aware of.

5:19

There are these different ways that we can maybe draw people into that and one of them is through producing this light, and this kind experience that we’re not going to necessarily understand.

But when you’re in the room, developing it together, it’s like there’s something that neither of you are necessarily putting into it.

It feels like there’s something emerging from that, that you don’t have control of… or … maybe I just don’t… I don’t know.

5:42

Jo: Yeah! [laughs in agreement]

5:47

Kate: I love your description of making a roller coaster, not just a track, like it’s like a full body experience.

5:55

Jo: Yeah

5:56

Kate: And I do feel that way when I’m listening to Jo’s cello.

Because in my neurodivergent world I would live very much in my head, and my body sometimes almost feels like a different country that I cross the border to go into to do the things I need to do, like use my hands.

So when when I can feel the music in sort of my whole body it’s quite like “oh, wow, I’ve got a body!”

So yeah, I sort of relate to what you’re saying about that, more than just going in your ears and being processed in that kind of way that we normally think of music.

6:32

Charles: I don’t remember where I got this but somebody said “sound is essentially an extension of touch”.

It’s like touch long distance and whether we’re hearing that or feeling that, it kind of says to me sometimes sound can be like time travel as well, if you’re listening a to recording…

6:50

Jo: yeah,

6:51

Charles: yeah, just crossing over and not keeping things in one narrow box.